This past winter, we highlighted the legacy of Matthaei’s famed yet almost forgotten botanist, Elzada Clover, the first female curator of our botanical garden. Along with her graduate student Lois Jotter, she was one of the first two non-native women to raft the entire Colorado River in 1938. The expedition was a national sensation at the time. If you are unfamiliar with Elzada’s story, you can listen to a podcast here with Melissa Sevigny, author of the 2023 book Brave the Wild River, which details this botanical expedition from the perspective of these two bold botanists.

As we learned from our deep dive on Elzada Clover, botany has historically been welcoming to women. At the turn of the 19th century, botany was the only scientific field that was socially acceptable for women to participate in. Sevigny shares on the podcast that “There was this very gendered idea about botany being this sort of wildflower gathering activity. So it was acceptable for women to do that, as long as they weren't going anywhere too scary, right?”

Sevigny ends the podcast with a note on the importance of sharing these stories of historical, female scientific exploration as she reflects on her early exposure to science in college.“People told me, “It’s really great [that you’re studying science], and we need more female scientists.” That was meant to be encouraging, but it started to make me feel lonely, like there was this void that I was supposed to fill. And the truth is, there is no void. I mean, women have always been doing science. They've always been doing science throughout history.” As we take March to celebrate Women’s History Month, we highlight three more groundbreaking female UM botanists whose collections and research were pivotal to our understanding of the botanical world today.

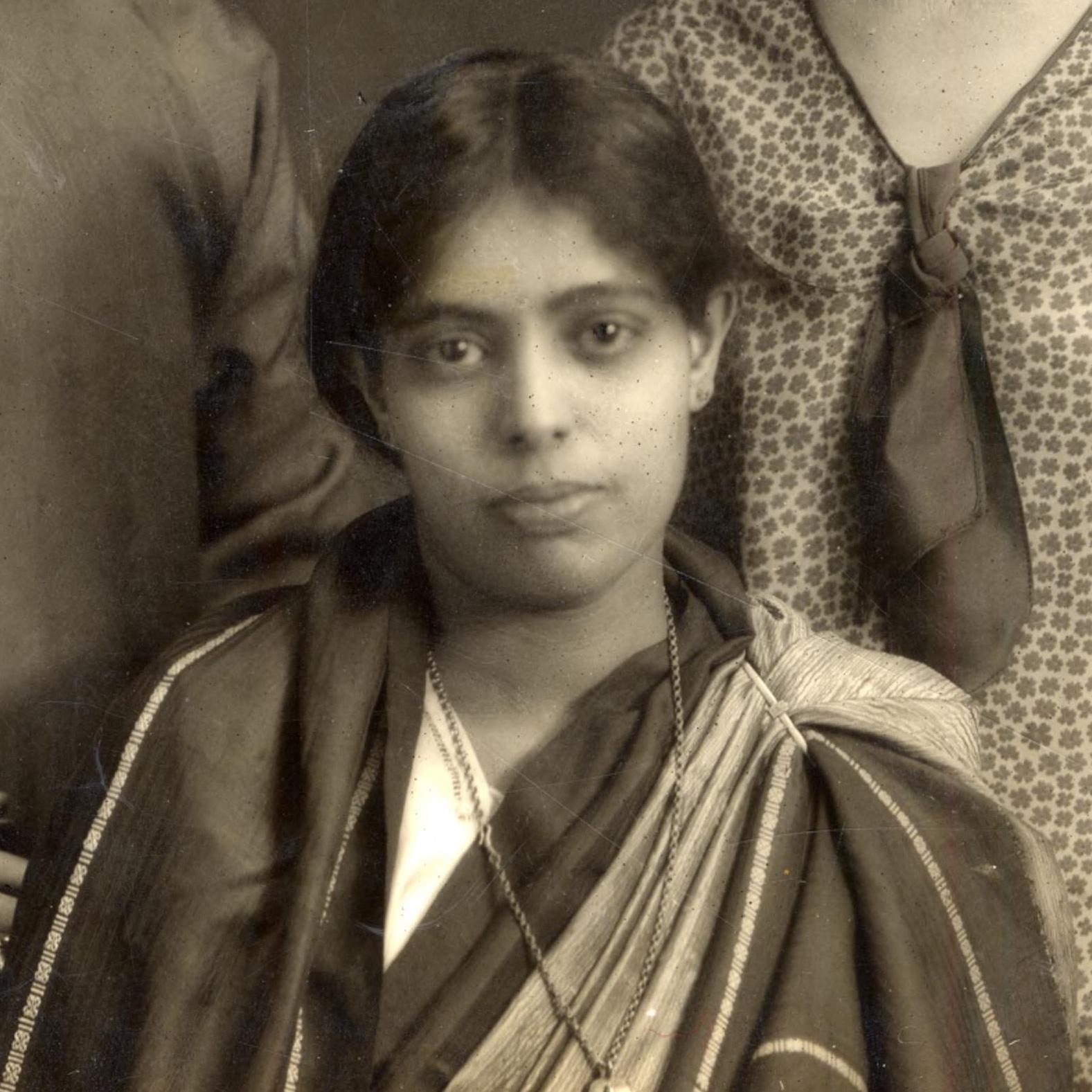

Janaki Ammal

Called the “first female Indian botanist,” or “the woman who sweetened India's sugar cane,” Janaki Ammal is known for her sugarcane hybrids, her contributions to the field of cytogenetics, and her advocacy to protect India’s biodiversity. In the 1920’s and 30’s, she was a graduate student at the University of Michigan, tending her experimental Nicandra fields at the original location of our botanical gardens, visiting the UM Biological Station in Pellston, and tromping through botanical fieldwork in her outfit of choice - a yellow sari, and a pair of muckboots. Her 60-year career is a testament to scientific dedication, exploration, and discovery, against all odds.

Ammal defied the standards for women of her time, caste, and country. Born Edavalath Kakkat Janaki Ammal in Thalassery, Kerala, she rejected the expected marriage path in favor of academic pursuits. She completed her undergraduate degree from Queen Mary’s College, Madras, and an honors degree in botany from the Presidency College. At this time, less than 1% of women in India were literate.

Ammal in Ann Arbor

Ammal received a rare opportunity to study abroad in the United States here at the University of Michigan. With the assistance of the prestigious Barbour Scholarship, a program that still supports women from Asia and the Middle East studying in the United States, she joined the botany department in 1924. She received her Master’s in 1925. Continuing her studies in cytology, she received her PhD in 1931. She was the first Indian woman to complete a PhD in botany in the United States. During her time in Ann Arbor, she lived at Martha Cook. She too worked alongside Harley H Bartlett, department chair at the time.

Home Sweet Home

Soon after graduating, Ammal returned to India, accepting a role as a geneticist at the Sugarcane Breeding Institute. There, she was entrusted with cultivating sugarcane breeds that could be grown in India’s climate, without reduced sweetness. Native sugarcane was not as sweet as imported varieties. She was the first scientist to cross sugarcane and maize successfully, developing a breed still grown today.

Botany During the Blitz

In 1940, she moved to London and began work at the John Innes Institute. She co-authored a groundbreaking botanical atlas titled “Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants.” This document cataloged the chromosome numbers of over 100,000 species and is still a touchstone resource for current-day plant scientists.

Building momentum in her career, Ammal stayed in London, becoming the first female scientist employed at the Royal Horticultural Society Garden at Wisley. In a 1940 letter to friend Miss Forcnrook, director of the Martha Cook dorm, she describes living in London in the constant threat of the war, “Meanwhile we live in great danger - air raids day & night - There goes the siren- I must seek shelter. You cannot imagine the time London is having, but we are all cheerful and getting used to bombs of every description.” Undeterred, she says in the same letter, "Life isn’t worth it without a sense of danger. ”At Wisley she worked on a diversity of garden plants, studying the chromosomal ploidy of Magnolias. To this day, Magnolia Kobus Janaki Ammal blooms each Spring at Wisley.

Home Again

In 1951, Ammal returned to India, asked by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to restructure the Botanical Survey of India. For the rest of her career, she worked in various positions within the Indian government. Ammal developed a keen interest in the ethnobotanical uses of plants, and the importance of preserving indigenous knowledge as integral to maintaining biodiversity. At a 1955 conference in Chicago titled “Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth”, she was the only woman in attendance. She spoke to the importance of indigenous ethnobotanical knowledge, writing in her publication for the conference “To examine the subsistence economy of India, it is first necessary to know the background history of the peoples who constitute the population of India and the relationships these peoples have with each other and their environment.”

Advocacy and Research As Long as She Lived

In her later years, she turned her attention to advocacy. A respected voice in science, she lent her expertise to the Save Silent Valley movement, a push to save a swath of tropical rainforest in Kerala slated to be flooded by the impending hydroelectric dam construction. She conducted a chromosomal survey of the valley's trees to preserve the rich information in the forest. Though she never lived to see the full result of her efforts, the project was abandoned and the forest was declared a national park in 1984.

In 1955, U-M granted her an honorary Doctor of Laws degree for her contributions to botany and cytogenetics. She was awarded a Padma Shri, a high civilian honor by the government of India at 80. She died seven years later, in 1984. As historian Vinita Damadaran writes, “A life of science, but lived in isolation, probably best describes her feminist choices. In the process she reshaped the internal frontiers of science, empire and nation in significant ways and helped to rethink the vision of India's national future as emerging from many sources that also embraced the tribal, the traditional and the ecological.”

Frieda Cobb Blanchard

Frieda Cobb Blanchard was a contemporary of Ammal, working as assistant director of the University of Michigan Botanical Gardens while Ammal completed her studies. Both women were geneticists, and the two formed a lasting friendship, evidenced by letters exchanged long after Ammal left Ann Arbor. A plant and animal scientist, Blanchard was the first to demonstrate Mendelian inheritance in reptiles through experiments with garter snakes.

Frieda also overlapped with Elzada Clover. A 1937 “SOS” letter from Clover in Colorado asks Frieda to consult on a labeling method, during fieldwork on a comparative analysis of two cacti species. Clover reports, "We are nearly wild from being tortured with spines as we work nearly every evening and Sunday. ”

the University of Michigan. Photograph by Harley H. Bartlett. Courtesy of Dorothy Blanchard.

A Lifelong Scientist

Born in Australia in 1897, Frieda was the daughter of Neil Cobb, known in his field as the father of nematology, and Alice Cobb, a former teacher. Frieda’s life revolved around science from a young age, as the family assisted her father in experiments on plant pathology and nematode worms. When she was 15, the family returned to the United States, spending time in Massachusetts, Hawaii, and Washington, D.C.

Blanchard at the Bot

Frieda came to Ann Arbor in the fall of 1916, at the encouragement of family friend and botany department new hire Harley H Bartlett. Blanchard began work on her PhD in plant genetics, focusing on the genus Oenothera (evening primrose). Oenethera was a genetic puzzle of the time, with plants not following standard rules of Mendelian genetics. Blanchard handled planting of oenothera at the Botanical Gardens, and her responsibilities soon snowballed. When Bartlett became garden director, he did so on the condition that Frieda serve as assistant, with a salary equal to that of an instructor. As local historian Grace Shackman writes in a highlight on the history of the old Botanical Gardens site on Iroquois place, “While Bartlett dealt with the public and with the university administration, Cobb managed the gardens’ day-to-day operations, taking over completely during Bartlett’s frequent absences.“

Frieda finished her PhD in 1920. Her dissertation, published in Genetics, supported Mendelian inheritance in certain Oenothera species, a key contribution to the field at the time. She continued as assistant director of the botanical gardens until her retirement in 1956, researching and publishing in plant and animal genetics. As Helena Pycior writes in Creative Couples in Science, “She also directed the growing of plants for class use and campus decorating; prepared budgets; accessioned plants and seeds; kept extensive plant records; and supervised the gardens, greenhouses, and employees, whom she also hired. She arranged exchanges, primarily of seeds, with other major botanical gardens.”

Scientific Sweethearts

In 1922 she married Fred Blanchard, a herpetologist who began his PhD the same year as she. Their solid scientific friendship was built in woodland outings to catch salamanders and newts, and their married life was one of synergistic scientific exploration.

For 22 years they placed scientific exploration at the center of their lives, even as they welcomed three children. Their symbiotic scientific relationship continued until Frank’s untimely death in 1937. Reflecting on their life together after his death, Frieda wrote "Beginning as graduate students, we had our offices in the same University building. Coming and going together, usually conferring at some time during the day, often working together, we consciously enjoyed the unusually close companionship this allowed us." Despite her significant loss, Frieda continued working at the gardens, raising their three children, and publishing their collaborative research efforts. A delightful vision from the observer piece, paints a picture of Blanchard, “who rode her bike to work before getting a car” riding home no-handed so she could eat ripe tomatoes.

Louisa Reed Stowell

While Elzada Clover was the first woman to become a botany professor at UM, she was not the first female instructor. Louisa Reed Stowell was the first woman hired to teach here at Michigan, though she was never given the proper title of professor.

Love for the Lens

Stowell was in the first two cohorts of women to enter UM’s scientific course when women were first permitted to join. In this program, she developed a love for microscopy and was enchanted with the world beneath the scope. Her drawings of the microscopic world were impeccably detailed, earning publication in Scientific American.

Over the summers, Stowell volunteered at the University Herbarium, helping to catalog their botanical collections. She was awarded her bachelor of science degree in 1876 and received her master’s in science the following year. Upon graduation, she was offered a paid position as a museum assistant at the herbarium, and contributed to developing their collections for 16 years.

Professor Stowell

Later that year, she was also offered a role as assistant in the microscopical laboratory.

Her responsibilities in this position soon grew beyond her title: Stowell began to teach, solely leading courses in botany, histology, pharmaceutical botany, and microscopy. She quickly became responsible for teaching half of the courses offered in the botany department.

Stowell's contributions in instruction likely helped Elzada Clover gain her footing as a full professor in botany. Clover’s advisor Harley H. Bartlett noted in a draft of Botany at the U of M through the first Century that while Reed-Stowell was successful in instruction, the “vexing problem of Mrs Stowell’s title” remained. Given a pay increase in 1879 commensurate with the pay of an instructor, the title never followed. Bartlett further noted that “The Regents, not knowing what to call her position, compromised by calling it nothing at all.”

The Michigan Alumnus of 1931 contains a criticism column, where a Marna Rosband writes “I notice the Alumni Catalogue does not list Mrs. Stowell among the faculty, but she did teach and she was paid by the University.” She describes how Stowell “mothered the girls of her time,” outfitting an area in the main hall with furniture from her own home where groups of women could congregate and rest. “It was the first thing that had ever been done for the girls, before there was a Women’s League even.”

Scientific Suffragette

A staunch supporter of women’s rights, especially in access to equitable education, Stowell spoke to over 800 at the inaugural International Council of Women (ICW) in 1888. On a stage graced with speeches from Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Frederick Douglass, Stowell spoke as a representative for the Western Association of Collegiate Alumnae, and voiced the demand for women to pursue the same course of study provided for males. Over her life she contributed more than 100 scientific publications.

Resources:

Bradford, M. (November 10, 2021). We Demand Education. Bentley Historical Library Magazine.

https://bentley.umich.edu/news-events/magazine/we-demand-education/

Ethirajan, A. &Mateen, Z. EK Janaki Ammal: The “nomad” flower scientist India forgot. (November 13, 2022). Retrieved February 28, 2025, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-63445015

Shackman, G. (2001, May). The Botanical Gardens on Iroquois. The Ann Arbor Observer. https://aadl.org/aaobserver/15253\

University of Michigan. (October 3, 1931). Alumni Association. The Michigan alumnus. [Ann Arbor].