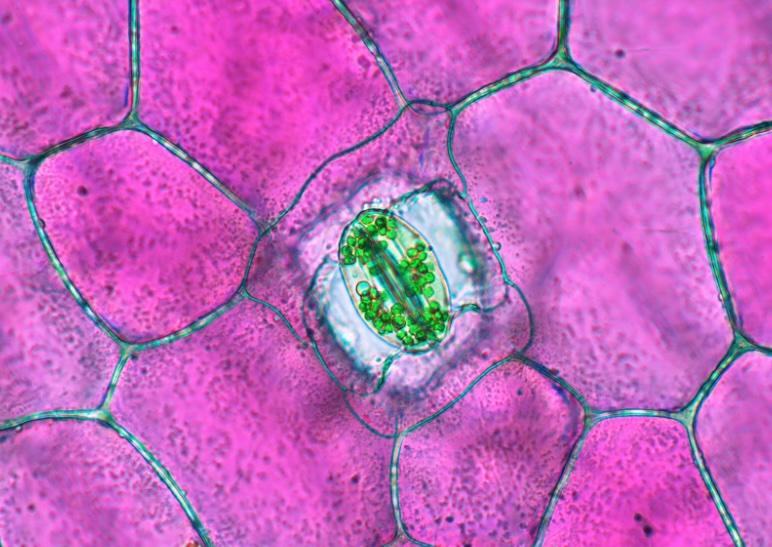

Microscope image of the stomata (a tiny pore that helps plants breathe) of a Moses-in-the-cradle Plant (Tradescantia spathacea)

Have you ever wondered what life looks like from a bug’s perspective? This February, “Leaves Under the Lens,” an experiential exhibit, is coming to our conservatory to showcase what is happening on a leaf at the microscopic level. Running through mid-April, this installation will pair plants in the conservatory with microscopic images of their leaf surfaces to explore the function of these tiny structures and textures.

The exhibit is curated by 4th-year Ph.D. student Rosemary Glos in collaboration with the Weber and Vasconcelos lab in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. It uniquely blends two of her interests: art and science. Glos studies how tiny plant structures influence interactions between plants and herbivores (the creatures that eat the plant) and mutualists (insects and other arthropods that help the plant out, sometimes even helping to protect against herbivores).

“My fork in the road as a young person was whether to go into art or science, and I chose science because I decided that it's a little bit easier to do science and art on the side than it is to do art and science on the side. But I think that artistic sensibility does pop up a lot in my science, and so I like to find ways to visualize and share my research in cool and compelling ways.”

Glos used a diverse approach to obtain these highly detailed photographs. Many of these images she took with the sort of microscope that might come to mind: a contraption with two eyepieces, knobs, and a surface for a slide. This is a light microscope that can help us see tiny things. But as Rosemary says, “Not all tiny things are created equal.” Some plant structures are so small they require an even stronger tool to see them. To create some of the images, she used a scanning electron microscope, which, instead of light, shines a beam of electrons at the leaf and makes an image based on how those electrons bounce off the surface.

Glos also used a tool called a micro CT scanner to actually take a look inside some of these plant structures, creating images that show a cross-section of the leaf. This tool lives at the UM Museum of Zoology and is primarily used to study preserved samples of animals: lizards, snakes, and fish. Using live plant material provided extra challenges for Glos. “Ironically, our samples were the first living things to go into that scanner, which was also kind of annoying because living things move, including plants. The leaves would do some of their natural movements under the CT scanner. Or they would move as they dried out and rehydrated. And the scans are long, almost an hour in some cases. And believe it or not, a plant can move a lot in an hour.”

Glos jokes that she is “in science for the pretty pictures.” And these close-up images of plants are stunning. But Glos has further hopes that this exhibit might prompt visitors to wonder about plants in new ways. Glos explains that scientists use the term “plant awareness disparity” to describe how people prioritize animals over plants in their worldviews. Glos explains that this phenomenon is understandable because, as humans, we tend to be drawn to things that look like us. “It can be a little bit harder to relate to plants,” Glos empathizes, “but plants are, in large part, the foundation of life on Earth, and they are beautifully, wondrously diverse.”

“Leaves Under the Lens” will help visitors appreciate this diversity of plants and see a perspective that is out of reach if you donʻt have access to a powerful microscope or a pair of antennae.

“I hope that this exhibit helps people take a second look at the plants around them and go from looking at, say, the plants in the conservatory as a green wall to instead this wonderful tapestry of different plant species with all of these unique and intricate features that you just have to look a little bit closer to see. Maybe it will inspire people to take a magnifying glass to the plants in their homes. You might just say, “Wow, there's all this that's been right under my nose this whole time, but I just couldn't quite see or notice it.”

The Leaves Under the Lens exhibit opens on February 1, and runs through Sunday, April 13, 2025.