In the summer of 1938, on a 41-day river trip, Dr. Elzada Clover and her assistant Lois Jotter sampled over 60 specimens of plants on the remote banks of the Colorado River, famed at the time as the most dangerous river in the world.

Stories are powerful. Stories are sometimes forgotten. And sometimes, stories are remembered for the same reasons that make them powerful. Perhaps this is the case with the story of Dr. Elzada Clover.

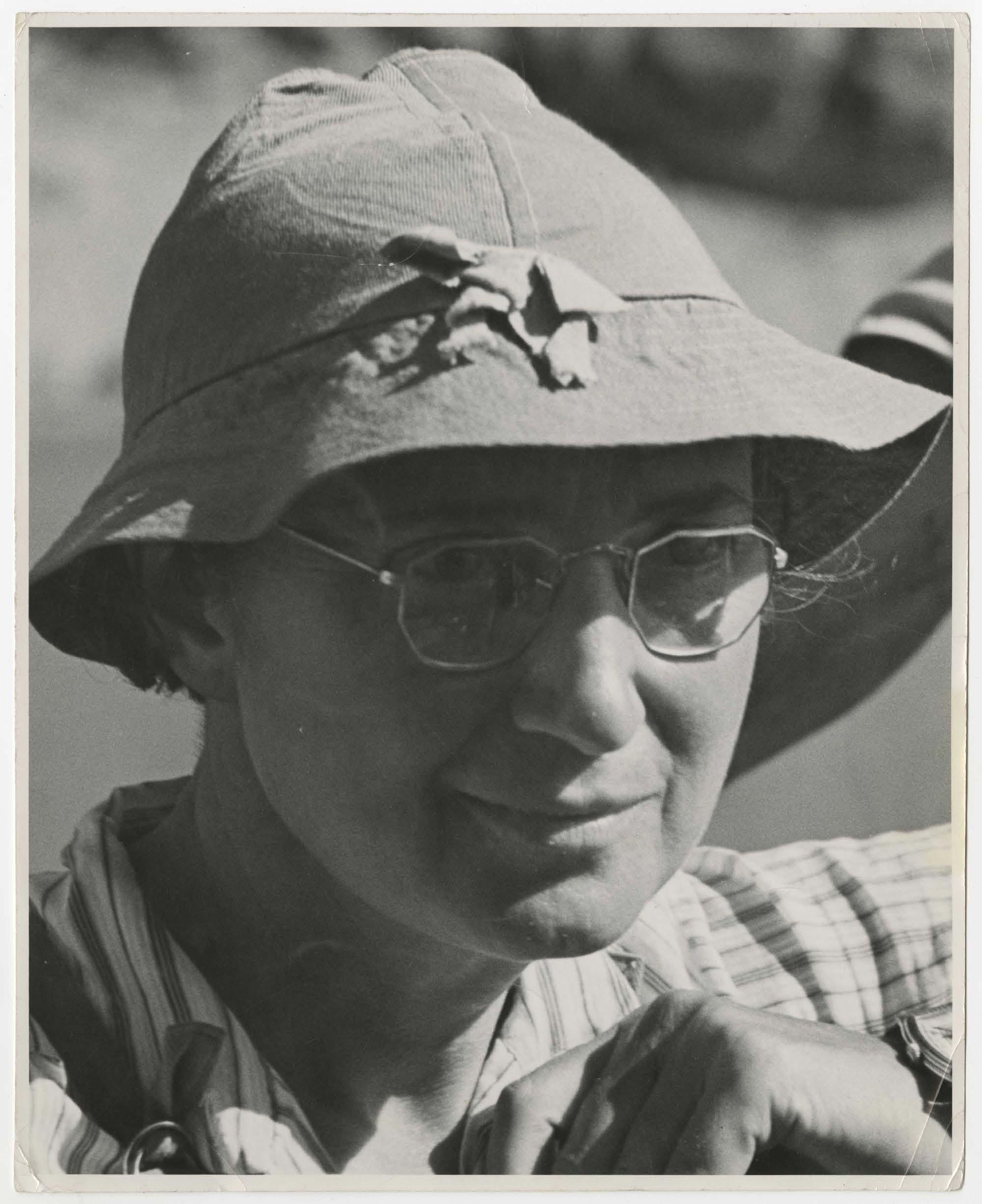

Dr. Elzada Clover was a unique woman who contained multitudes. Brazen botanist, first female Matthaei Botanical Gardens curator, first female UM botany professor, and first known non-indigenous female river runner of the Colorado River, these identities are all connected by a deep and unwavering love of plants. While her career is dotted with many “female firsts,” her story is best understood by recognizing her life as one long love letter to the botanical world.

In “Brave the Wild River,” a 2023 recounting of this journey by Melissa Sevigny integral to bringing this story back to life, she describes Elzada as "a tall woman, active, robust, dramatic, daring, perhaps just a little bit wicked. She drank whiskey. She could swim, fish, hunt, and ride a horse. She preferred to describe her own code of behavior as ‘gentlemanly’ rather than ‘ladylike.’”

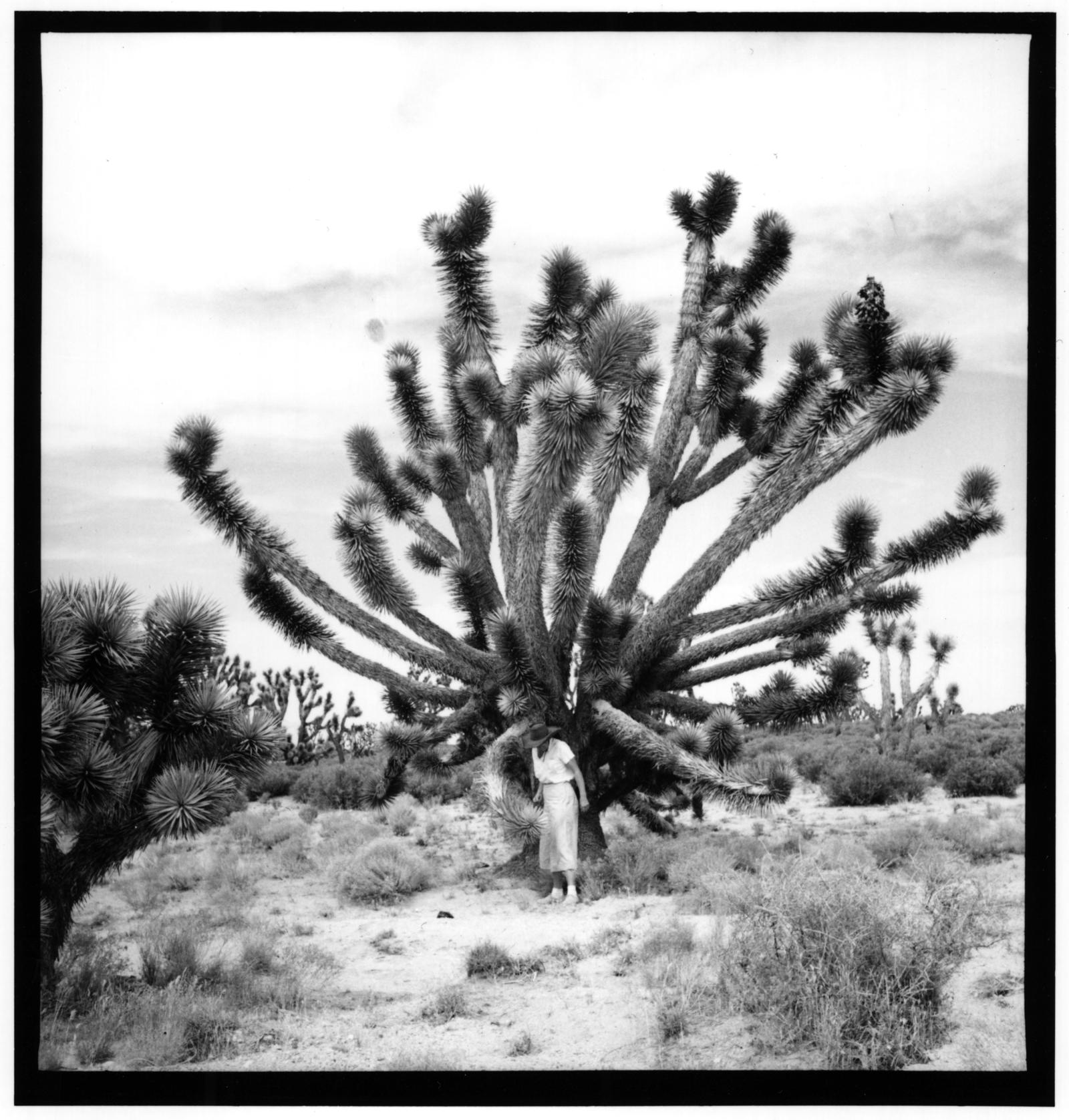

Elzada Clover’s legacy lives on through the barriers she broke in the scientific world. It also lives on materially in the pads and spines of giant cacti. As one enters the arid house at the Matthaei Botanical Gardens, a Prickly Pear cactus (Opuntia tomentosa) stands tall on the left, sporting vibrant green pads covered in fine spines. In further beds, a dagger cactus (Stenocereus griseus) shoots towards the ceiling, near a bed with an old man cactus (Pilosocereus leucocephalus), all grown from specimens she brought back from a later trip to Guatemala.

Her legacy lives on, too, in the minds of many of her students. Just a mile from our Botanical Gardens, Jane Myers, a former student of Elzada’s, still has stories to tell about her eccentric botany professor. In one such memory, Clover drives down the centerline of a northern Michigan road. From there, she could better see the plants growing on each side.

Botany Bound

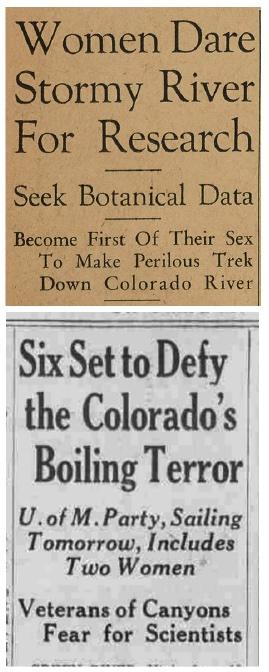

In 1938, traversing the Colorado corridor was rare for anyone. The journey promised trial by sun, rattlesnake, and white water at best and drowning, injury, and death at worst. Despite these risks, Clover was set on botanizing the remote banks of the Colorado River.

At first, Clover intended to explore the area by pack mule. But after a chance meeting with boat enthusiast Norman Nevills, who was interested in developing commercial rafting along the Colorado River, the idea for a botanical boat journey was born.

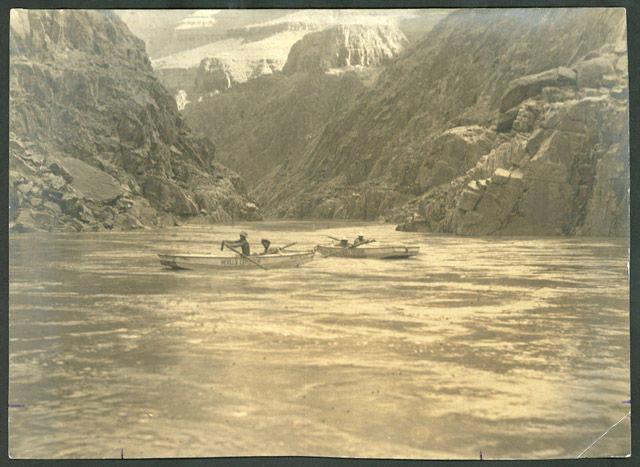

On June 20, 1938, at 42, Elzada Clover climbed aboard a small handmade wooden boat named the “Wen,” crafted by her companion and boatman Norm Nevills. Ahead of her lay miles of turbulent, muddy river water boxed in by canyon walls. While the trip would gain national attention, Elzada Clover did not have her eyes set on fame but on the riverbanks and side canyons of the southwest, yet unexplored by botanists.

At 42, she was the oldest member of the crew. As 600 miles of rugged water stretched before her, a life of education, persistence, and botany stretched behind. Elzada was born in 1896 in Auburn, Nebraska, seventh in a line of nine children. She grew up working the family farm, known for her storytelling and humor. After her mother's death, Elzada went with her father to Texas, where he had purchased land around the Rio Grande, needing a change of scenery. Here, Elzada’s fascination with cacti blossomed. Hearty and persistent, perhaps she saw herself in their quiet resilience. After seven years of teaching and serving as a principal in Texas, Clover returned to Nebraska to attend her old school, now a State Teachers College. There, she received her BA and then launched to Michigan, where she enrolled as a student in the Botany department, earning her master’s and then her PhD. Her thesis work focused on the plants of the Rio Grande.

Botany Boys Club

Elzada and Lois were exceptional before they set foot in the ruddy waters of the Colorado. By 1938, Elzada Clover already had her doctorate, and Lois Jotter was well on her way to earning hers in a time when fewer than 15% of all PhDs went to women. Historically, Botany was a field unusually welcoming to women. Collecting flowers in fields was considered a demure enough activity for womenfolk.

Plant presses, plant collections, and botanical illustrations were all a go. However, this tolerance dried up when it came to further pursuits in the field. After graduating, Elzada struggled to find work in her field. Elzada was at first turned down for a full professorship at UM. In his diary, her advisor and the department chair, Harley H. Bartlett, wrote in frustration, “Elzada is not wanted because she is a woman, although she has been unusually successful as a teacher of the younger students, and we need her precisely for that.” He kept her on at Michigan as a lecturer at the time. He was supportive but wary of the Colorado expedition. But because he wouldn’t hesitate to do it himself, he didn’t try to stop Elzada. However, the trip was not funded with departmental support. She applied for funding for the expedition and secured a small grant from Rackham, but not for the total sum. The rest of the trip came from her pocket and the pockets of her companions.

Before the 1938 expedition, Clover had already spent much time botanizing in the American Southwest. Her initial plan for exploring the Colorado corridor was to go by pack mule. However, a chance meeting with boatman Norm Nevills while botanizing in Mexican Hat, Utah, in 1937 changed the course of this expedition. Wanting to open commercial rafting in Colorado, Nevills proposed a voyage by boat. If he successfully led women safely through the river, he reasoned this would deem the expedition safe and encourage vacationers to brave the river, too.

Clover and her Crew

The expedition was known as the Nevill’s expedition, though both Norm and Elzada made decisions and were looked to as leaders of the group. At the launch in Green River in June 1938, the crew consisted of six rafters and three boats. Norm and Elzada were joined by Lois Jotter, Elzada’s graduate student assistant; another UM graduate student, Eugene Atkinson, artist Bill Gibson, who photographed the trip; and Norm’s assistant, geologist Don Harris. Norm constructed three boats for the journey: the Wen, the Botany, and the Mexican Hat. Although Nevills had experience running expeditions on the San Juan River, no one in the party had run the Grand Canyon before.

This story primarily lives on thanks to the detailed journals kept by many expedition members. In the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, two black leather journals embossed with “Record” on the cover hold Elzada’s detailed account of the journey. Her script is curly, sometimes rushed, thoughts and observations jotted on precarious banks with hands tired from lining boats and collecting plants. Sometimes, she wrote from the boat itself. On July 3rd, she noted, “I am sitting up on the stern of the boat, and the waves are bouncing me so I can hardly write. This is a beautiful country. Deep red cliffs.” Her “Is” looks like “2’s,” and she writes “with” using the medical notation of a c with a line across the top.

Women on the Water?!

The trip received national attention, and only a little was encouraging. Newspapers nationwide ran stories calling the expedition reckless, many of them missing the scientific aim of the expedition. The only other woman known to have attempted the trip was Bessie Hyde, who, a decade earlier, set out for a honeymoon river trip with her new husband Glenn and never returned. Their boat was discovered intact, but no trace of the couple was ever found. Buzz Holstrom, a known river runner, journeyed the Colorado River the summer before the Nevills expedition embarked, making news as the first solo runner of the Green and Colorado rivers. A Saturday Evening Post story detailed his expedition. In a question regarding Glenn and Bessie Hyde's disappearance, he remarked, "Women have their place in the world, but they do not belong in the Canyon of the Colorado.”

But both women knew the risks. In her journal, Elzada wrote: “I know that we will be cut off from any hope of getting out in case of accident, illness, or fright. We have all decided we wanted to come. My chief hope is that nothing I may do will hinder the success of the trip.”

Lois Jotter packed all her belongings away in case she did not return from the river.

The story of Elzada and Lois as botanical pioneers is nuanced. This false notion that women were not tough enough to run the river was further reinforced by another false idea that the river was a wild, “unexplored” place. This notion ignored the history of the eleven federally recognized tribes who have called the great river home for millennia. These Indigenous peoples intimately know the plant life of the area, even the plants “first” recorded by Elzada and Lois on the expedition. As Sevigny writes, "The field of botany suffered because of racism and colonialism. As Native languages and cultural practices vanished under the U.S. government's systematic eradication efforts, information about plants and their uses also disappeared."

Elzada was known never to insist she was the first woman down the Colorado, always making clear she was the first non-indigenous woman to raft its ruddy waters alongside Lois Jotter.

Women’s Work

Running the river was hard work. The crew all worked together to row and line the boats around rapids, all while enduring scorching heat, turbulent waters, and the pressure of steep canyon walls; for much of the journey, the only way out was through. Off the water, Lois and Elzada's work was not finished. In the evenings, after cooking for the entire crew, well into dusk and dark, Elzada and Lois collected plants. In the mornings, Elzada and Lois rose before dawn, collected samples with cold fingers, and then prepared breakfast. While good mornings boasted warm biscuits, when food ran sparse between river access points, they ate grape nuts molded in the middle from getting wet in the boats. On July 3rd, Elzada wrote: “Lois and I pressed plants. It took until 10 o'clock. We were to have breakfast ready at 6:00 am. We got up at 4:30, had breakfast ready, and bedrolls done by 6. Men are all sleeping hard. I photographed them and then played “I can’t get him up” on the harmonica.”

The two women did not seem phased by this division of labor, with Elzada writing plainly: “The men depend on Lois and me for so many little things. Mirrors, combs, finding shirts, first aid, etc. Just as men always have since Adam.”

But she did have a keen sense of humor and wrote playfully about the sleeping men on the trip. “They looked like pupas lying there in a row in their sleeping bags, " she wrote one morning. Another morning, she wrote, “At 4:40, I took a picture of the sun and of the “sons” not rising. Lois and I are nearly always up first, getting our bedrolls put away and our cooking done. This A.M., I pressed plants, too. “

Close Calls

The river trip was no lark. In just the first half of the voyage, the crew endured hardship- roiling waters that threatened to swallow the boats whole and rising waters at night that tugged at their bedrolls, forcing them to scurry further up the bank in the middle of the night. Some rapids were so harrowing that Nevills ran them solo, having the others walk and meet him downriver.

One boat, the Mexican Hat, was swept down the current, feared to be lost to the river forever. Lois and Don jumped into action, hopping into another boat to chase after it. Interviewed about this experience when the crew reached Lees Ferry, Lois recalled: “We went through some rather big waves, I suppose ten to fifteen feet or so, and in one or two places, it seemed as if the boat were about to tip over, especially when the force of the waves was strong enough to pull the oars from Mr. Harris’s hands.” Eventually, they found calmer water, and Lois glimpsed the boat bobbing in an eddy downstream with its oars sticking out. A testament to its craftsmanship, the boat was undamaged, its contents damp but unscathed. The sun setting, Don headed upstream to alert the others. Lois stayed back with the boat and spent the night alone beside a crackling fire. Unphased, she reported, “Except for the little red ants whose area I had disturbed, the pack rats in the bush about two feet away, and the noise of the rapids and waves, my night was really uneventful.” The New York Times headline ran: “Miss Lois Jotter of Nevill Expedition Spent Night on the Canyon Ledge With Red Ants and Pack Rats.”

Boat-side Botanizing

Although limited by space, time, and the ability to keep samples dry, Elzada and Lois documented over 60 species, including four previously undescribed species of cacti that helped establish the collections in Matthaei’s Arid House. Elzada noted in her journal, “You’ve no idea how difficult it is to keep the mind on mere plants when the river is roaring, and the boats are struggling to get through.” They categorized the plant life of the canyons into five distinct zones along the sandy riparian up to banks where small trees and shrubs grew. Their collected specimens live here at the UM Herbarium at the Smithsonian and in several other botanical collections.

These sheets survived much to exist today: wet conditions, scorching heat, and even a period when a large portion was thought to be lost at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Sent up on a pack mule to be delivered to the University while they completed their last leg, it never made the trip. Clover and Jotter returned to Ann Arbor disheartened that much of the work they risked their lives for was lost to the canyon. Incredibly, the missing press was found months after the women had returned to Michigan by their now friend and fellow river runner Buzz Holmstrom as he set out to run every rapid between Wyoming and Lake Mead. Eyeing an odd stack of paper at his campsite at Bright Angel Creek, neat but for a mess of green growing out of the sides, he identified it as the missing plant press and sent it off to Michigan. Their final plant list included four previously undescribed cacti species. Their final plant list included four previously undescribed cacti species: Echinocereus canyonensis, a hedgehog cactus; Echinocereus engelmannii, a strawberry cactus; Opuntia longiareolata, a beavertail cactus; Sclerocactus parviflorus, a small fishhook cactus. This survey remains the only complete record of plant life along the Colorado River before the damming of the Colorado River, which drastically shifted plant communities along its banks.

Off the Water

Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter published their complete plant list in The American Midland Naturalist in 1944. Without ever using the word, Clover and Jotter were thinking on an ecosystem scale, considering how and why certain plants were distributed throughout the Colorado corridor.

Lois went on to earn her PhD and become a wife and mother. After her husband’s death, she accepted a position teaching Botany at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Elzada rose in the ranks to become a full Matthaei curator in 1957 and a full professor of botany in 1960, teaching classes on campus at the UM Biostation and leading the first-ever class to take place at the Botanical Gardens. An introductory botany course, it was popular and inspired many to pursue the field.

She was a beloved professor of students who both revered and perhaps feared her. She had an intensity about plants that was palpable to all. Her student Jane Myers says of her teaching style: “She was somebody with such intense interest in all things botanical that you did not want to disappoint her. She had a strong personality and a deep respect for her students. She treated you like an equal or a colleague. She had energy and determination and believed in what she was doing.”

Her adventurous spirit never waned, and the herbarium holds testament to her later trips to Haiti, Guatemala, Mexico, and several returns to the American Southwest. As curator of the Botanical Gardens, she was pivotal in developing the cacti collection. Three cacti in the Arid House at Matthaei can be traced to specimens she sampled in Guatemala.

Sevigny ends her recounting of the river trip by bringing the importance of their barrier-breaking to the present day. “A recent study found that it will be another two decades before women and men publish papers at equal rates in the field of botany, a field traditionally welcoming to women. It may take four decades for chemistry and three centuries for physics. Stereotypes linger of scientists as white-coated, wild-haired men, and they limit the ways in which young people envision their futures. In a famous, oft-replicated study, 70 percent of six-year-old girls, asked to draw a picture of a scientist, draw a woman, but only 25 percent do so at the age of sixteen."

Elzada Clover went to the river for science. But she also went to the river with broad curiosity and rode its waves with reverie. In her journal, she once wrote, “The night was so beautiful that I couldn’t sleep,” and when the journey ended, she wrote with longing for the river. "I’m so lonely for it now I can hardly stand it. Could scarcely keep from crying as I stood on the boats today and felt them rising up and down with the waves.”

Once almost forgotten, the story of Elzada Clover has now been written about many times. This telling is informed and influenced by “River Rat,” an excellent retelling by Kim Clarke of LSA’s Heritage Project, AADL’s fantastic Elzada Clover highlight this past year by Amy Cantu, and extensively by Melissa Sevigny’s brilliant book, “Brave the Wild River.” This piece was also made possible by the incredible archivists at the Bentley Historical Library, who care for the Elzada U. Clover Papers, a collection of her journals, writings, and publications. These materials made it possible to include the words from Clover herself, who told the story of the journey as she lived it.

To learn more about Elzada Clover, we invite you to visit our exhibit Down the River with Elzada Clover, at Matthaei Botanical Gardens from November 29, 2024 - January 24, 2025.