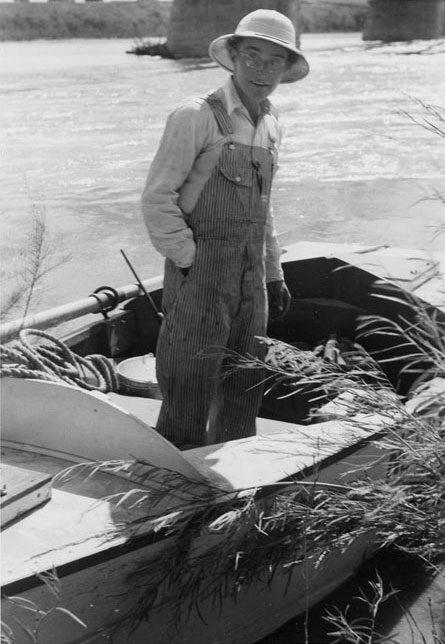

Elzada Clover at the start of the trip. Image: Special Collections Department, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

What was botanist Elzada Clover up against in 1938?

“Elzada isn’t wanted because she’s a woman,” wrote University of Michigan botany department chair Harley H. Bartlett in his diary over the executive committee’s refusal to promote Elzada Clover beyond instructor in 1938.

“For fame, for glory, for thrill, or for swell obituaries, they are going down the river,” commented the Salt Lake Telegram in an editorial on Clover’s Colorado River expedition, calling the team “foolish, reckless and heedless.”

“I think Elzada is the best man in the bunch,” concluded expedition guide Norman Nevills in his journal.

Women’s History Month in March is about looking back to acknowledge achievements. It’s also about looking ahead to forge new paths using the past as a springboard. In today’s story, we take a closer look at the groundbreaking work of Elzada Clover, University of Michigan professor of botany and assistant curator at Matthaei Botanical Gardens.

Clover’s 1938 expedition goals were simple: to explore and identify new species of plants unique to the region. In her funding proposal, Clover wrote, “This part of the West is inaccessible because of a complete lack of roads and trails. It has never been explored botanically and for that reason everything collected will be of interest.”

The initial plan called for hiking into the canyon and down to the riverbeds. River guide Norman Nevills, for whom the expedition was named, convinced Clover to undertake a water route.

Over 43 days–36 on the river–the team of six traveled 666 miles from Green River, Utah, to Boulder City, Nevada through extremely treacherous waters, 900 foot deep and unexplored canyons and areas of remarkably stark, beautiful terrain. Where rapids were too violent, they portaged their 600 pound boats over land.

When Nevills set off to traverse a mile long rapid, Clover, wracked with worry, wrote in her diary “I was petrified … I am really scared to death for him.” She described his acceleration through the rapid: “Watched him around a bend which he made in nothing flat, sometimes I couldn’t see him at all, at others just his head. I am here with the boats but I can’t stand the suspense so am tying their sterns & shall go over about a mile and a half of very rocky trail and see if all is well.”

They observed plant life in astonishing locations: species in high places, clinging to canyon sides, scattered where springs supported tropical-like varieties, and others spread about due to floods and high water. Clover wrote, “Here is a case where drought vies with flood waters in exterminating plants struggling for existence in a trying situation.”

The team identified five plant zones, 50+ species of desert plants, and discovered four new species: Grand Canyon claret cup with a red-purple flower, fishhook cactus with small flowers and curved spines, strawberry hedgehog cactus, and beavertail prickly pear. The cactus Clover collected formed the basis for what is now Matthaei’s desert house collection.

Successfully concluding the daunting expedition, Clover and graduate student assistant Lois Jotter became the first women to boat down the Colorado River. Clover went on to become assistant curator of Matthaei Botanical Gardens in 1957 and professor of botany from 1960-67.

For the history of the expedition, check Kim Clarke’s fascinating story.

Katie writes for Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum